The major fissure concerning the controversial military commissions at Guantánamo Bay is no longer between civil liberties and national security. It’s between the commissions and the intelligence services, with the future of the 9/11 war crimes tribunal hanging in the balance.

On one side are both the commission prosecutors and defense attorneys, all of whom grapple in different ways with bringing justice to defendants who spent years in the brutal black box that was CIA custody. The prosecution in particular is laboring to send the message that, after years of stop-and-start proceedings, the commissions are now a viable, professional complement to federal courts.

On the other side are the CIA and the FBI, which have gone to extraordinary lengths to prevent information about the detainees – particularly about their torture in CIA custody – becoming public. The intelligence and law enforcement agencies’ equities at Guantánamo, at a minimum, conflict with the successful military prosecution of the detainees. At worst, they undermine the venue meant to provide a final dispensation for alleged post-9/11 war crimes.

And the agencies may now have overplayed their hand.

Last week, defense attorneys for 9/11 co-defendant Ramzi bin al-Shibh revealed that the FBI surreptitiously compelled a classification specialist assigned to them to sign documents indicating he would inform on the defense teams.

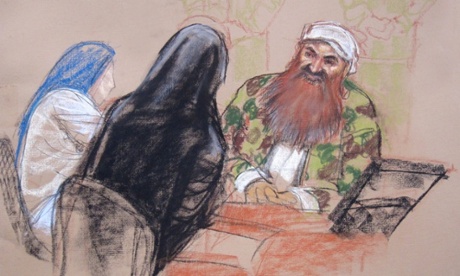

The revelation crowded out the pre-trial hearings scheduled to take place last week. The judge in the case, Army Colonel James Pohl, isslowly unfolding his own inquiry into whether the FBI is investigating the commissions’ defense attorneys, seemingly over the release of an unclassified manifesto by accused 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

Barring unforeseen events – and, admittedly, the military tribunals have been nothing if not a series of unforeseen events – when the 9/11 military commissions resume in June, it will not be to clear through the thicket of motions that must be resolved before an actual trial can commence, but to examine the extent of the FBI’s penetration of the defense counsel. One of the defense lawyers in the case doubts the trial will get under way by 2016.

The apparent investigation into Mohammed’s defense attorneys was only the latest example of intelligence or law enforcement agencies asserting their prerogatives over the 9/11 tribunal. Last year, the CIA remotely muted the courtroom when a lawyer for Mohammed attempted to discuss conditions at the agency’s now-shuttered secret prisons. The agency’s ability to mute the proceedings was a surprise to Pohl, who issued acease-and-desist order.

Additionally, rooms used by the 9/11 defense lawyers for discussions with clients featured listening devices disguised as smoke detectors, confirming years of suspicion on the part of the defense that their conversations were under surveillance. The culprit was the FBI. Furthermore, the defense teams have faced a huge breach of their email data, which the Pentagon says was inadvertent.

“At this rate, it looks less and less likely that the 9/11 defendants will ever be brought to trial,” the Miami Herald editorialized.

If and whenever the trial commences, surreptitious surveillance of the defense and interference with the proceedings may also jeopardize any convictions or sentences obtained, according to legal observers.

“If the allegations are true, the FBI’s tapping of a member of the defense team for information on the defense’s case, something unimaginable in federal court proceedings, could conceivably lead to the defense asking for a mistrial,” said Karen Greenberg of Fordham University Law School.

“But as the trial isn’t yet under way, and mistrials assume that the trial is under way, it is more likely that you would get a request for dismissal based on outrageous government conduct.”

The prosecution is attempting to press on. A lawyer added to the team specifically to address the FBI issue owes Pohl a filing by the end of Monday responding to the defense’s assertions. The chief prosecutor, Army Brigadier General Mark Martins, insists he can proceed to jury empanelment by year’s end, despite the mounting complications caused by the intervention of the FBI and CIA.

And the biggest clash between the CIA and the commissions is just beginning to unfold.

Last week, in a different case, Pohl ordered the CIA to produce, through the prosecution, specific information about what the agency’s secret, torturous detentions after 9/11 actually meant in practice. As Pohl is also the judge in the 9/11 tribunal, the 9/11 attorneys promptly vowed to use Pohl’s ruling as a precedent to force the CIA to turn over similar information in their case.

The CIA must now decide whether it will co-operate and provide information that it has fought strenuously for over a decade to keep secret or if it will resist a judge’s order and jeopardize the prosecution of the 9/11 defendants. And it must make the choice while facing the partial public disclosure of a Senate inquiry into its post-9/11 renditions, detentions and interrogations.

Last week’s courtroom events may have made the intelligence agencies’ role in the tribunal more stark, but they have hung over the tribunal like a shadow. Were it not for the treatment the 9/11 defendants suffered in CIA custody, the tribunal would likely have concluded by now, as a large swath of their attorneys’ pretrial motions concerns establishing the extent of their pre-trial incarceration and its legal implications.

The intelligence value the CIA reaped from torture was minimal, according to senators who investigated it. The impact on the only legal proceedings designed to bring a semblance of closure to 9/11 may be far greater.

No comments:

Post a Comment